(Bloomberg) — Many Sri Lankan voters who backed President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s election bid three years ago are now struggling to make ends meet. His government is spending to ensure that support continues even as reserves and finances dwindle.

That could lead to Colombo asking for more loans and aid from China and India given that the government has vowed to stay away from International Monetary Fund assistance that often comes with conditions for fiscal and monetary reform.

National polls are due in 2023 at the earliest, and Rajapaksa is buying time with spending until the economy springs back. He’s unveiled a $1 billion relief package last month and raised civil servants’ salaries while promising to double farmers’ income to prevent a widespread backlash from taking root.

It’s a high-risk move for the Sri Lankan economy with nearly $7 billion in dollar-denominated debt maturing this year and the government already calling in favors to reschedule loans.

There’s also the question of inflation, which is at the fastest pace in Asia, due to failed harvests, import restrictions, and high global prices of key commodities. Rising demand for imports along with the reopening of the economy could pressure foreign exchange reserves when there’s still little coming in from overseas remittances and tourism.

“There has to be a very solid plan, with payments due and reserves where they are, and especially if we are going without the IMF,” said Lakshini Fernando, macro-economist and the co-head of equity research at Asia Securities in Colombo. “Transparency on policy also needs to improve, both for investors and the common man, in order for tensions to ease and confidence to be built.”

Here’s a snapshot of the groups who have supported Rajapaksa and are coming under pressure from the economic tailspin:

Farmers

Farmers are a vote bank for Rajapaksa, and some 20% of Sri Lanka’s population are involved in agriculture. They have protested against his plan to promote organic farming by banning imports of chemical fertilizer, as tea and rice crops started to fail last year.

“In the black market urea prices shot up,” said R. Kumarasiri, a vegetable farmer from the southeastern Welimada area. “People who had some money were able to cultivate using chemical fertilizer. People who cultivated are now getting high prices. It is people who could not cultivate that really suffered,” he added.

The government denied the ban was to limit expensive imports although the ruling was later revoked to avoid a backlash and $200 million was offered in compensation last month to the farmers. At a recent rally, Rajapaksa said he would double the income of the farmers.

“In these difficult times, we have afforded you every relief on every occasion,” he told the gathering. “I am committed to do whatever is necessary for the farming community.”

The damage is done though, with the government estimating a 20%-30% drop in rice paddy output in the current season with local prices soaring.

Low Wage Earners

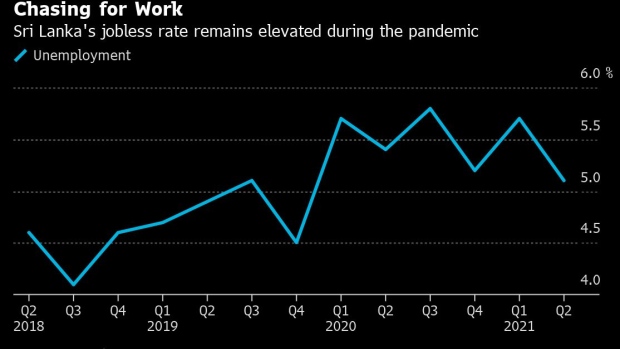

Informal workers make up about 70% of the workforce and mostly come from the Sinhalese majority who voted for Rajapaksa amid promises for populist goodies, Buddhist nationalism and enhancing security after the Easter Sunday attacks. Many lost their jobs as the pandemic closed businesses in tourism, manufacturing and agriculture. Unemployment rose to a high of 5.8% in 2020 and remains elevated.

“They stopped paying salaries,” said Raj Kumar, a 69-year-old father of three who lost his job at a bakery in the central hill town of Hatton. “It is very difficult. All prices are high. We can’t afford milk in our tea,” he added.

Surging food and fuel prices have lifted Sri Lanka’s inflation well past Pakistan to become the fastest in Asia. The central bank raised interest rates last month for the first time in three meetings to rein in the jump.

High prices and unemployment is likely to keep the proportion of people at Sri Lanka’s $3.20 per day poverty line high this year. The World Bank estimated the 2021 share of the poor at 10.9% of the population, falling slightly from a projected 11.7% in 2020.

Small Businesses

Sri Lanka’s economy is powered by over a million small and medium-sized enterprises that account for 75% of all businesses. A significant section of the business community supported Rajapaksa in the elections with his pledges for firm leadership of the economy.

With the forex crisis, businesses are spending more rupees to secure U.S. dollars to pay for imported materials that are used to manufacture everything from garments to rubber gloves in Sri Lanka. There are delays in clearing ships at Colombo port as banks don’t have enough dollars to collect the goods on time, leading to extra costs.

The operating environment is no better. The central bank has roped in lenders to finance fuel imports to avoid an electricity crisis and keep the economy running uninterrupted after multiple lockdowns.

“We have to fix this economic problem very fast before people get agitated and get into the streets,” said M. Ranasinghe, a business consultant from Colombo, who runs a small hotel. “The confidence people are having in the government is going down day by day.”